During the filming for God Save the King, one of the crew members and I were having a conversation. He remarked, “Okay, you’ve completely re-educated me about the birth of Jesus of Nazareth, especially the correct date—so tell me something—is the same true for Easter?”

What he meant by this question was, “We’ve got Easter wrong too, don’t we?” My answer was, “Yes, although not quite as bad as his birthdate/Christmas.”

You see, “Easter” isn’t a biblical holiday either. Both holidays, commemorating the birth, and later death and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth are the victims of “tradition” and not in a good way.

The word Christmas simply did not exist at the time the Bible was written, and therefore can’t be found in the Bible. The single word English word Christmas, which is a contraction of Christ’s mass, or “mass for Christ,” started to be used somewhere around the middle of the 14th century. The word Christmas is not found in the Bible. It is not there—ever—and to use the word Christmas to describe the birth of Christ is a kind of disingenuous reverse engineering. The same is true of Easter.

Not surprisingly, the word Easter isn’t in the Bible either.

But wait! Many will exclaim. What about Acts 12:4?

And when he had apprehended him, he put him in prison, and delivered him to four quaternions of soldiers to keep him; intending after Easter to bring him forth to the people.

[Acts 12:4 KJV, emphasis added]

The simple truth is that the English word Easter in the King James Version is a mistranslation of the Greek word pascha (Strong’s #3957), that means Passover. Pascha is used 29 times in the New Testament, and is translated correctly 28 times (in the KJV), so there is no valid reason whatsoever to translate it “Easter” in Acts 12:4. Most other Bible versions translated the word correctly.

Etymologically, the English word Easter is a derivation of the Akkadian word Ishtar, the name of the ancient Sumero-Babylonian goddess of love and fertility—hence the connection to bunnies, eggs, fish, and other pagan fertility symbols.

As of the early 15th century, the English word Easter did not exist yet. At that time, the equivalent word pascal (clearly derived from pascha meaning Passover), was the commonly used term. One of the earliest uses of the English word Easter that we can verify was when Dutch navigator Jakob Roggeveen discovered what he would name “Easter Island” on April 2, 1722. Based upon these two facts, it appears that the word Easter came into common use during the 16th century.

Not only are both holidays the victims of often unyielding man-made tradition, both are also the victims of syncretism. Syncretism is the practice, predominantly by Roman Catholics, but also by other large denominationally based strongly institutionalized church organizations, of combining doctrines and practices that “appear” Christian, with non-Christian practices of similar appearance. For example, in the case of Easter, because resurrection is a kind of (re)birth, it is connected with fertility, and thereby Ishtar becomes Easter. Or, in the case of Christmas, the birth of the Son, is vaguely connected to the (re)birth of the sun after the winter solstice. Mix well, codify it, and maintain that salvation relies on absolute adherence, and you get Christmas.

An in-depth article about the true nature of the resurrection will have to wait, so a summary will suffice for now. In preface, let’s remember one of the foundational principles of God Save the King.

“The third most important issue surrounding the traditional nativity story is the very fact that it is ‘traditional’. The modern version of the traditional nativity story is the product of 2000 years of Christian ‘tradition’ as opposed to diligent biblical and historical research. In particular, this tends to mean that the nativity is viewed as ‘Christian’ phenomenon despite the fact that it occurred within a conspicuously Jewish context.”

Tim Keyes. Resetting the Chronology for the Birth of Jesus of Nazareth, p.5.

The exact same thing can be said about Easter. The common “Easter” story is the product of 2000 years of Christian “tradition” as opposed to diligent biblical and historical research. In particular, this tends to mean that Easter is viewed as a “Christian” phenomenon despite the fact that it occurred within a conspicuously Jewish context. While the death, resurrection and ascension of Christ is inarguably the centerpiece of the Christian faith, one can make strong biblical argument that “Christianity” didn’t exist yet, as of the crucifixion. One will never truly understand the amazing depth of the death and resurrection of Christ until we return it to its Hebrew context, especially the Jewish spring festivals—the feasts of Passover (Pesach), Unleavened Bread (HaMatzah), and Firstfruits (Bikkurim).

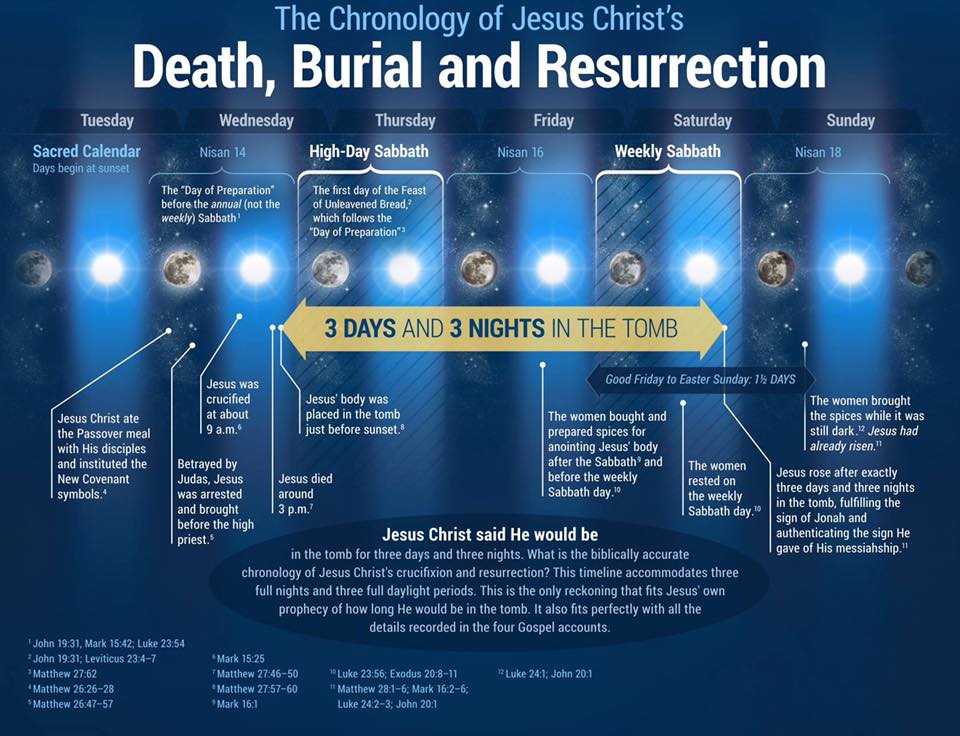

As the “lamb of God” (John 1:29), Jesus was crucified at the same time as the Passover lambs were being slaughtered—on what was known as the Day of Preparation, prior to sunset on the15th of Nisan that would mark the official beginning of Passover. As the “bread of life” (John 6:35) he was buried “during” the feast of Unleavened Bread—again in the Day of Preparation. The Jews had to make sure he was dead and buried before the official start of the feast in order to maintain ritual purity (John 19:31). And as the “firstfruits of the them that slept” (1 Corinthians 15:20) he was raised from the dead on the feast of Firstfruits. If we miss the unmistakable Jewish context of these events, we miss the point entirely. From God’s point of view, the whole idea was to be somewhat cryptic yet as conspicuous as possible. An observant Jew should never have missed the deliberate and significant connection of the Lamb of God, Bread of Life and Firstfruits occurring in conjunction with Hebrew feast days.

This year (2020) we have a unique opportunity to see the accurate chronology of the crucifixion. Working backwards from the biblical record we read that when the women came to anoint his body on Sunday morning, he was discovered to have been already risen. Read that again carefully. The Bible does not say he was raised on Sunday, but rather clearly implies that he was raised on Saturday afternoon/evening, before the women discovered the empty tomb.

Continuing to work backwards, if we utilize the sign of Jonah described by Jesus himself, that he would be dead and buried for three days and three night (72 hours), this means he died on Wednesday afternoon. It is impossible to squeeze “three days and three night” (72 hours) between “Good” Friday and “Easter” Sunday.

To go through all of the details requires a book not an online article, but the parallels are nothing short of extraordinary, and it all hinges upon the Jewishness of the event.

Jesus was not raised from the dead on Easter Sunday, he was raised from the dead on Saturday, the Jewish Sabbath, but was discovered to have already been raised on Sunday. Again, like “Christmas” to call Jesus’ resurrection “Easter” is a kind of disingenuous reverse engineering. The word isn’t biblical in its origin, and even if it were, the common usage is not properly applied.

The fact that Jesus’ death and resurrection match the Jewish feasts so precisely is part of the evidence used to determine that he was also born on a Jewish feast day (see my essay An Appointed Time).

The death and resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth has been called the greatest story ever told. This is understandable for it truly is the foundation of our faith. But Jesus could not have died and been resurrected if he had not been born. The birth and sacrificial death of Jesus of Nazareth form the bookends of the story of the most significant person in human history, Jesus of Nazareth, the son of God, the Messiah of Israel.

God save the King. Long live the King.