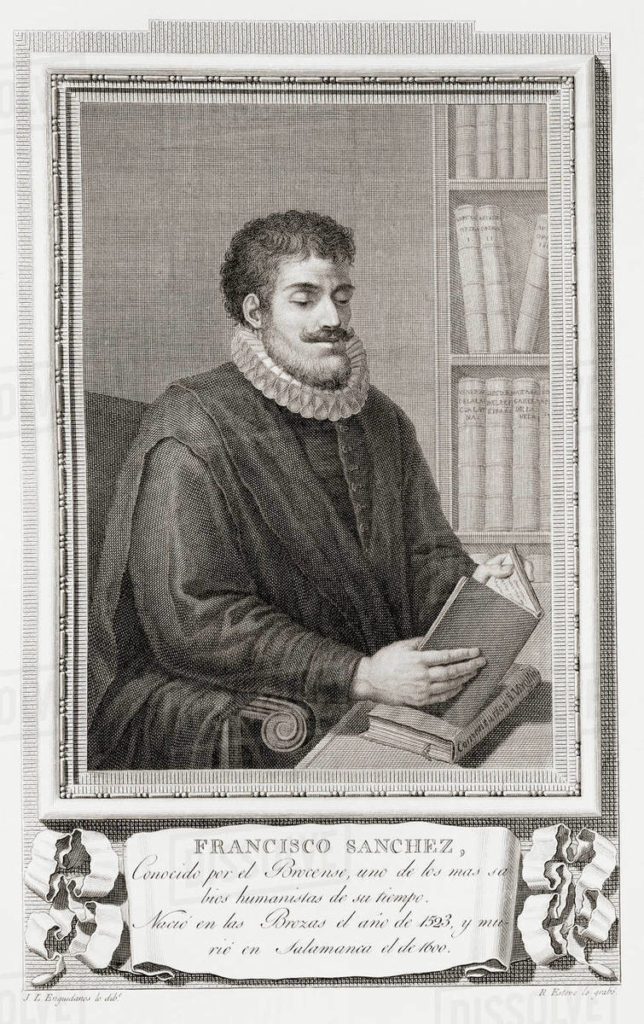

Francisco Sánchez de las Brozas, known as ‘El Brocense’, “the great and outspoken philologist at the University of Salamanca,” was born in Brozas, province of Cáceres, Spain in 1522, Francisco Sánchez was the son of noble parents, but they had little money. He was only able to study thanks to the financial support of relatives. He served at the court of Queen Catherine I and King John III of Portugal in Lisbon until the death of the presumptive heir, Princess Dona Maria Manuela, due to hemorrhage from childbirth. He left the court and studied Art and Theology at the University of Salamanca but did not finish. He attempted to achieve the chair of several departments at the university, but often failed, finally receiving the chair of Rhetoric in 1573.

In 1584, he had his first brush with the Inquisition. Why? His students reported him. Why again? He had criticized certain features of the nativity as depicted in church paintings as lacking biblical support. Which features? Specifically, that Jesus was not born in a stable, nor were his parents turned away by an innkeeper. He boldly stated that Mary gave birth in a private home belonging to friends or relatives.

El Brocense defended his critique in writing, which became a part of the official Inquisition records. As a result, the files of the Spanish Inquisition contain one of the earliest historical/exegetical arguments contradicting the traditional nativity story.[1] On this occasion, he was exonerated.

Long after he retired, in 1595, a new inquisitorial process started. El Brocense died on 5 December 1600, isolated in his home under the house arrest imposed by the Inquisition.

Sanchez also believed that the Magi visited Bethlehem at least one year after Jesus was born.

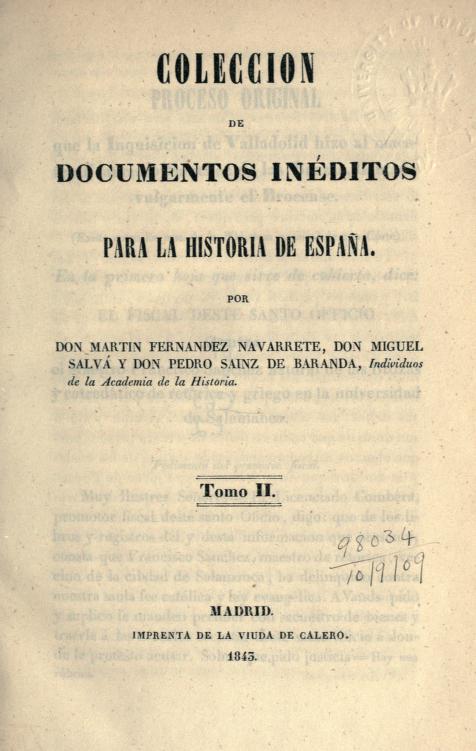

[1] Copies of the Inquisition proceedings against Francisco Sánchez can be found in Antonio Tovar and Miguel de la Pinta Llorente, eds., Procesos Inquisitoriales contra Francisco Sánchez de las Brozas (Documentos para la historia del humanismo español 1; Madrid: Instituto Antonio de Nebrija, 1941) and earlier by Martin Fernandez Navarrete, Miguel Salvá, and Pedro Sainz de Baranda, eds., Colección de documentos inéditos para la historia de España (vol. 2; Madrid: La Viuda de Calero, 1843). [Pictured.]